We have a tendency, after great disasters, to say we need to push through, to get back to “business as usual.” But what does that even mean when the world we knew has been upended? Of course, those who are concerned with money, the money machinery never pauses. It never stalls. But the emotional bruises, the deep severing that happens in times like this, after Melissa here in Jamaica, are often overlooked.

I just ended a class early today. Only three out of fifteen students showed up, all of them carrying the weight of family in the devastated areas. T’s family is in Mandeville; thankfully, he has heard from them. G’s grandparents in Trelawny were unreachable for days; her mother only just managed yesterday to reach them and bring them supplies. M, Another student has relatives in Black River; for days her family were on jitters, but now they got word that they are but practically homeless due to the severe damage to homes. “We cannot focus or concentrate,” one student admitted.

They came to class as I did , showing up, yes but it was heavy. Each one spoke of exhaustion, of numbness, of not knowing how to speak the unspeakable. One student said simply, “Miss, I really don’t know how I’m feeling.” That, to me, was the most eloquent response of all. She doesn’t know because the feeling itself is too large, too raw.

So we sat with that heaviness. We talked a little. We were grateful for the extra week the university has given us, since classes were cancelled during the storm’s preparation. But the truth is, many of us still don’t have electricity or running water. Some students live on campus, others off, but none of us are untouched.

It is not business as usual. And it will not be business as usual for a long time.

To pretend otherwise is to force people to swallow their feelings, to bury their pain beneath routine. But the feelings remain: the anxiety, the sense of loss, the disconnection.

Despite all our gadgets: our phones, our laptops, our Wi-Fi — we were cut off. When the power went, when the towers went down, when the batteries died, we realized how fragile all this supposed connectivity really is. The technologies that claim to unite us failed us. They could not bridge the silence, could not bring our loved ones closer.

One student said it felt like COVID all over again — that same isolation, that same uncertainty, that same feeling of being suspended between fear and waiting. And they were right. Melissa brought back the dread of those days: the quiet streets, the locked rooms, the worry for the next meal, the exhaustion of not knowing what tomorrow will bring.

This is trauma upon trauma.

For a society like Jamaica, Melissa exposes again our fragility. Kingston and St. Andrew may have been spared the worst, but almost everyone here has relatives in the rural areas that were devastated. We know mothers without diapers for their babies, women without sanitary supplies, families without clean water or food. And we know, too, that disasters bring out the predators, the exploiters, the opportunists, the perverts who prey on the vulnerable. This is their time: when people are bewildered, desperate, searching for food and water. The community, once our safety net, becomes splintered. The children are not watched. Everyone is just trying to survive.

It is not business as usual.

We must acknowledge this tremendous trauma, trauma upon trauma upon trauma. Because Jamaica has never truly healed. We have not healed from the original wound of slavery, nor from the centuries of colonization that followed. Even before Melissa, the media showed us how many of our people still live in conditions of semi-slavery, neglected, forgotten, barely surviving.

So how do we begin to heal?

First, we acknowledge that the trauma exists. We name it. We say, something in me doesn’t feel right. My head is heavy. I feel jittery, tired, unmotivated. I can’t rest. I can’t focus. I am hungry all the time, or unable to eat. These are not small things; they are the body’s language for pain.

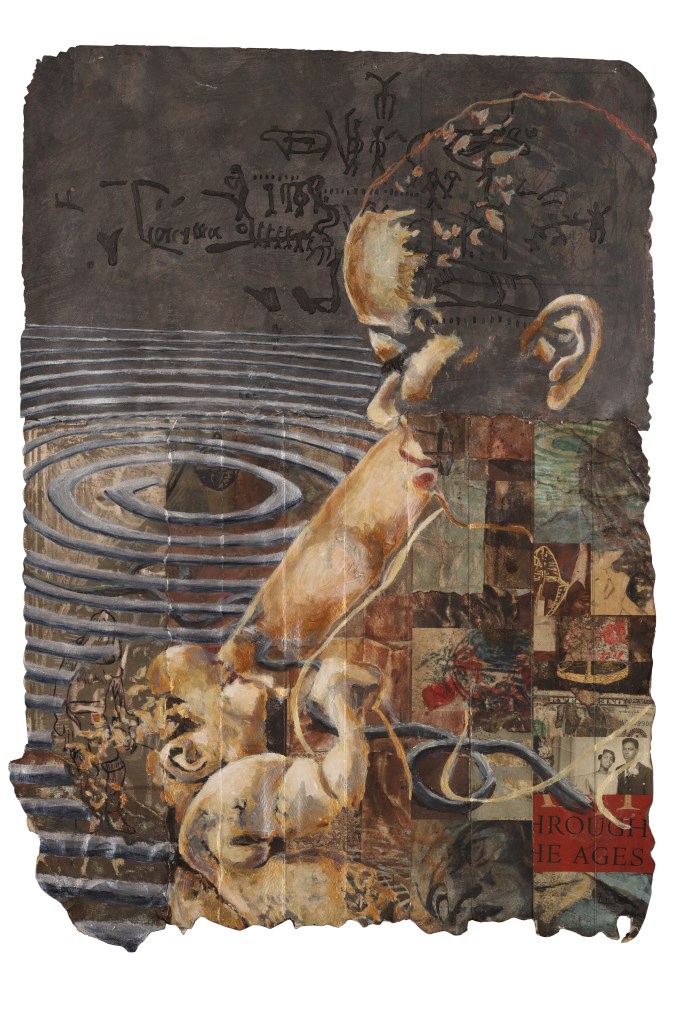

In my class, I gave my students crayons and paper and told them to draw how they feel. Because the arts are a form of therapy. And all those children in the hardest-hit areas, those whose schools have been destroyed, they, too, need art therapy, poetry therapy, dance and movement therapy. They need someone to say to them:

We know you feel unsafe. We know the sound of the hurricane still lives in your head, still vibrates in your bones. We are here to help you feel safe again.

We must learn to speak and act with compassion. We must provide spaces of solace where one can sit quietly, listen to music, and do nothing. No deadlines, no demands, only the slow, necessary work of healing.

It cannot be business as usual, my people.

We cannot continue being traumatized and re-traumatized, whether by natural disasters like Melissa, by centuries of enslavement and colonization, by inequality and indifference, by pandemics that isolate us, and by technologies that promise connection but deliver silence.

We need to heal. We need to pause.

We need circles of love and healing and spaces where we can shout our anguish, our despair, our frustration, our betrayal. We need time to sit with ourselves, to comfort ourselves, to forgive ourselves and the world.

We need moments of kindness and compassion where we can simply be present with what we feel, and breathe through it together.

It cannot, it must not, be business as usual.