The life of a writer is to share her work and trust that it finds its audience. I’ve just returned from a three-week European tour—unexpected, yet affirming. While I’ve long known my work is taught in Europe, I had not been invited to share it in over a decade. So, when the Serendipity Institute for Black Arts in Leicester, UK, invited me to present my documentary Conversation –Jean Binta Breeze, I felt an immense joy. Jean was the first female dub poet, a dear friend, and a voice I refuse to let fade.

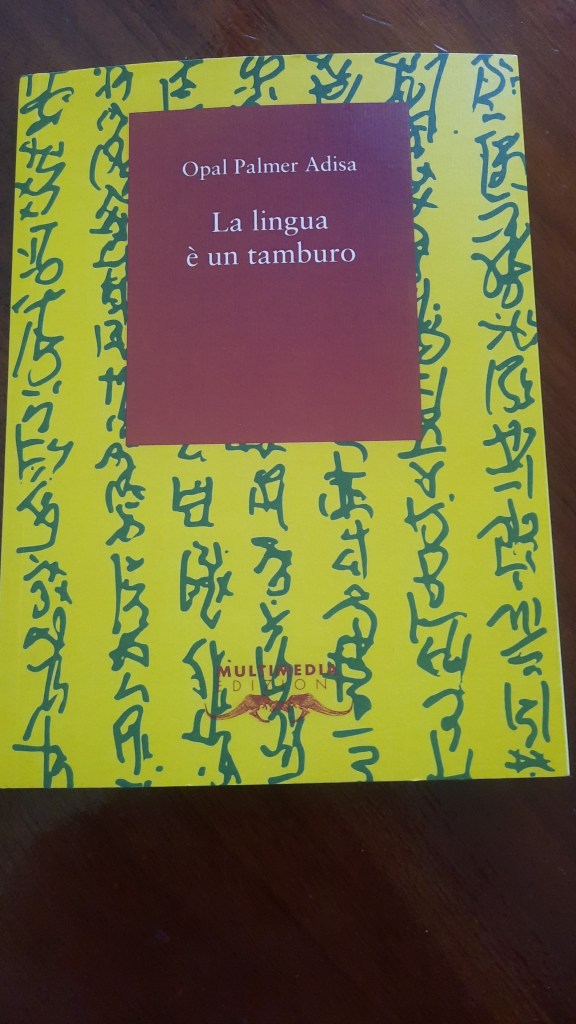

That invitation opened new doors. Casa della Poesia, a thirty year literary organization committed to amplifying diverse voices, invited me to share my work. To my surprise, they informed me that they were translating a selection of my poems and that I had been awarded the Regina Coppola International Literary Prize. I had worked with Casa della Poesia before, years ago, as part of the Bosnia Peace Festival, but I didn’t realize they had planned visits to three schools and a bookstore event to launch my translated collection, La lingua è un tamburo.

People often assume a writer’s life is glamorous—and, at times, it is. I travel, share my work, and connect with audiences in places I never imagined visiting. Yet, writing is also solitary. You create in isolation, unsure if your words reach anyone, let alone touch them. Without awards or royalties to reassure you, doubt can creep in. But these invitations reminded me that my work still carries weight in places I had never even considered.

At a bookstore just outside Naples, I read to an overflowing audience—one of their largest. That night, they sold more books than at any previous launch. Yet, the true highlight wasn’t the accolades or sales; it was the engagement with students. In three different high schools, we had deep discussions—about the Middle Passage, colonialism, gender, and history. In Salerno, a predominantly European, middle-class city, I found young people eager to engage with Caribbean history and black identity. Their depth and insight moved me to tears. Clearly, their teachers had prepared them, translating my poems and guiding discussions. My work had become a permanent feature in Italy, a country with a small black population and even fewer Caribbean voices.

Fifteen or twenty years ago, when I visited Europe, everyone associated Jamaica with Bob Marley. Today, I encounter a new generation, one less familiar with our icons but still eager to learn. My poems—whether about No Woman, No Cry or Emmett Till—remain teaching tools, bridging gaps in knowledge and fostering dialogue. Creative writing, poetry in particular, has the power to break barriers, to create understanding where there was none before.

From Italy, I traveled to Spain. Elisa Senario, who once wrote her dissertation on my work, is now a professor. She and her students have been translating my short stories from Love’s Promise, and last year, we held a Zoom lecture. When she learned I would be in Europe, she invited me to the University of Granada for a symposium. Meeting her students in person reinforced an unexpected lesson: translation is more than words—it is history, context, and culture.

To my fellow Caribbean writers who feel unseen: seek audiences in Europe. This journey reminded me that my work is not only read but also embraced. There is an eager readership willing to engage with the complexities of our histories and experiences. Our stories matter. We must share them—fully, honestly—without assuming they will be ignored. The students and audiences in London, Italy, and Spain have reaffirmed what I had nearly forgotten: my work remains relevant and has currency. I am profoundly grateful for the opportunity to continue sharing it.

Watch:

https://www.facebook.com/share/p/15T2iq9aKF/

I am so happy for you. Keep up the good work. Keep on keeping on….

Daisy

LikeLike